Dayglo Doom: Byrds Hit the Wall in 1980

Dayglo Doom: Byrds Hit the Wall in 1980

|

| He was a friend of mine: Notorious Ex-Byrd appears surprised when his even notorious-er ex-Byrd Twitterbro blocks him. Result: draaaaa-ma! |

Rogan knew all of this—that these men would be forever linked in spite of their protestations to the contrary—before anyone else, which is why a chapter like “The Dark Decade” was necessary for understanding the bond they shared in a post-Byrds world.

But this compartmentalized, Byrds-eye view of things in which each of our heroes rode the crest of a never-ending wave of fame was upended, if not convincingly slapped down, on December 31, 1979. The exactness of the date is symbolic here, not indicative of any historical moment. But by 1980, in the bifurcated wakes of punk and disco, the implications of an ever-changing musical landscape were laid bare. Ahead lay a future much more uncertain—and indeed, for Gene Clark, more perilous—than it had ever been. No longer America’s Answer to the Beatles, the Byrds were now representative of the old guard, forced to prove their relevance. A “Dark Decade” indeed.

A time to break down

In 1965, the Byrds were a household name: before the year ended, they had achieved two back-to-back #1 singles, both of which were performed the Ed Sullivan Show on December 12, 1965 (55 years ago this month). They toured England; met, befriended, and been given the thumbs-up by Beatles. At that time they rivalled the Beach Boys for the title of best American band.

Fast-forward 15 years, and the ex-Byrds found themselves struggling for relevance in an inhospitable musical milieu. Think of what was popular in 1980. How could, say, Gene Clark’s music have possibly found an audience amid the peak years of disco, punk, post-punk, new wave, and synthpop? Let’s take a quick look at the two Clark-penned songs released in 1980 (on the City LP), both of which found him lagging behind the times. McGuinn Clark & Hillman’s ‘Won’t Let You Down’ was a fine song, yes, but in many ways a self-conscious throwback to his signature song, ‘I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better.’ It broke no new ground and seemed formulaic; a little stiff, both in execution and production. Similarly, ‘Painted Fire’ was a ‘50s-style rocker that felt forced, unnatural. Both songs lacked the immediacy and power of a track like Split Enz’s ‘I Got You.’ That song used its ‘60s influences as a springboard for a newer sound, while MCH seemed tethered to the same roots they’d helped establish in the first place.

In the end, all of the ex-Byrds either struggled as solo artists, clung to each other in various configurations, or simply dropped out of the rock spotlight altogether: musical variations of the fight-or-flight impulse.

At one time, the Byrds rode alongside Bob Dylan like some righteous, suede-jacketed posse; a point further underscored by their decision to cover Dylan’s finger-pointing pronouncement of generational shift, “The Times They Are a-Changin’.” By 1980, however, they could have quite easily been on the targeted end of the finger.

A personal recollection (1979-1980)

At the time, I was oblivious to all of this, and deep in thrall of The Byrds’ Greatest Hits, which I bought in 1979, when I was 15. At that time, I was also listening to the Beatles (together and solo), Dylan, Blondie, the Police, the Who, Buzzcocks, the Jam, and the Sex Pistols. I remain fond of these bands—alas, some more than others (e.g. The Who became a lifelong obsession; the Police, a mere footnote). The passage of time and gradual exposure to thousands of other artists, cultures and styles of music played a large role in how things ultimately played out—which is, I’m quite sure, how it is for all hardcore music fans.

The Byrds, however, have never gone out of rotation for me. They’ve never been left behind. I love their contradictions, their paradoxes, their disparate personalities, their quirks; I love their ability to reconcile opposites and conflicting impulses, even if only for two minutes. From the day I purchased The Byrds’ Greatest Hits, I was obsessed with not only the music, but also the look of the band, as reflected on the bottom of the back cover, which featured small black & white pictures of the first four LPs. In terms of what I considered a cool look, it was all there (although by 1979 the fashions were over a decade behind, which reveals much about my sensibilities).

|

| The back cover of The Byrds’ Greatest Hits LP, with the four cover images that have fascinated me for decades. Below: The fantastic four, in colour! |

I have related the above story not for purposes of indulging in nostalgia-induced wankery, but to explain how hard it was to reconcile my feelings about the look and sound of the Byrds—the elements that made me a lifelong fan—with my subsequent experience with the then-current option: McGuinn Clark & Hillman. I remember feeling great anticipation ahead of their appearance on American Bandstand in support of their debut LP (the AB video of the performance used to be on YouTube, but has since been removed). I mean, come on, these were my guys, after all, but it wasn’t some old documentary, it was happening today. Now. This, was a new band for me to get into. When Dick Clark introduced them, I was very excited.

And then they mimed to “Don’t You Write Her Off.”

By the time the song ended, I already felt a profound sense of disappointment. It was the kind of disappointment that is so devastating and personal when one is young, and a hero has failed.

Rightly or wrongly, the resulting stigma from that performance stuck with me for decades. Shortly after that appearance on AB, I recall seeing the then-newly released McGuinn Clark & Hillman LP in the shops. I picked it up, carried it around with me as I walked through the store. But in the end, I put it back on the rack. When the followup, City, arrived in 1980, I was much more decisive: I looked at the cover, thought it looked dumb, and quickly forgot about it. I was moving on to other things. My tastes included the nine albums grouped below, all of which remain very dear to me.

In some cases, visual makeovers were used as declarations of relevance, examples of which include Linda Ronstadt’s new-wavy bob/dayglo lettering ensemble on the cover of Mad Love, and the Grateful Dead’s windblown/disco-suit look on Go to Heaven). Elsewhere, big shot Billy Joel sounded much like an entitled, arrogant asshole you always took him for in his unfocused response to New Wave, ‘It’s Still Rock and Roll to Me.’ Billy smacks down up-and-coming musicians (without naming them, of course), trendy fans, and music writers...all in 2:57! It’s even got the requisite Saturday Night Live sax solo, a staple of late ‘70s records. Sooo cutting edge.

Only rarely were transitions as effortless as those undertaken by Mike Kellie (Spooky Tooth) and Alan Mair (The Beatstalkers), veterans of the UK’s 1960s rock/psych scene, who went on to create fine music with Peter Perrett in the Only Ones, during the height of punk.

Elsewhere, big-name acts like the Rolling Stones carried on, seemingly too big to fail. Let’s face it, Emotional Rescue (1980) was no Let It Bleed. It was a middling effort; an excuse to mount a large, lucrative tour. To this day, the Stones remain a draw, in spite of having distinguished themselves as rock’s most notorious example of diminishing returns. There are many ways to interpret history, but in terms of artistic integrity, I believe that the Stones more or less hit the wall in 1980, and maintained their “superstar” designation by dint of their past triumphs, with the assistance of generational momentum.

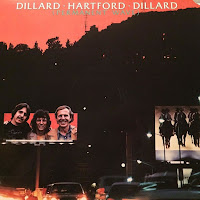

Turning to those in Gene’s orbit, one need only look at what Doug Dillard was up to in 1980, to get a sobering sense of how 1960s artists were coping with changing times.

On Permanent Wave (pictured at left) a 1980 LP by Dillard Hartford Dillard, Gene’s erstwhile duo partner Doug Dillard presented a truly bizarre 1980 remake of 1968’s evergreen “Something’s Wrong.” If you would seriously proffer this as superior to the original, or even a worthwhile experiment, I shall have to ask you to step outside. Compared to this schlocky embarrassment, Firebyrd seems like a bona triumph on the level of No Other.

Meanwhile, to a man, Gene’s erstwhile co-pilots in the Byrds found themselves hitting severe turbulence in 1980:

DAVID CROSBY

When David Crosby’s love for drugs eclipsed his love for music (epitomized by the now-infamous hash-pipe incident, in which Crosby halted a studio jam to mourn the loss of broken drug paraphernalia), a planned 1980 Crosby-Nash LP was ultimately released as a Nash solo outing, Earth & Sky. And Crosby still didn’t get the hint.

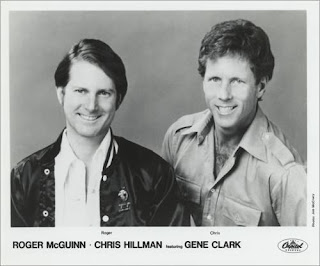

ROGER MCGUINN, CHRIS HILLMAN

After Gene Clark drifted away from Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman during sessions for the City album (released in early 1980)—a move that saw his image removed from publicity handouts, his name reduced to third billing—the duo sputtered in mediocrity, and eventually called it a day...but not before they had seen fit to record the 100% Clark-free McGuinn-Hillman LP, which they foisted upon punters later on in the same year. I never bought that one, either.

|

|

MICHAEL CLARKE

Michael Clarke’s improbable run as “ex-Byrd to Appear on the Most Hit Songs in the 1970s” (as a member of Firefall) ended in—you guessed it—1980. Sadly, it was Michael’s addiction to alcohol that led to his being replaced on Firefall’s 1979 tour. His last album with the band was 1980’s Undertow. Apart from an appearance on an early-‘80s Jerry Jeff Walker LP, Michael spent the remainder of his career as a minor leaguer on the bar circuit.

And what about Gene? Did he have a plan after leaving MCH?

He hooked up with old buddy Jesse Ed Davis, went to Hawaii, came back and recorded gorgeous demos on the still-unreleased “Glass House Tape”—but few people would have been aware of this information. To anyone at the time, Gene’s days as a major label artist had come to an ignominious end; he was no longer viewed as a marketable star. Remember, only six years before, his songwriting on the Asylum Byrds album had earned him the right to record 1974’s No Other—a testament to his talent, in spite of the fact he had not scored a hit single as a solo artist. This was an astonishing fall from grace, exacerbated by the fact that he deserved so much better, and lived to see things get so much worse.

Interestingly, McGuinn, Crosby and Hillman would mount successful comebacks before the end of the decade. After a wise tactical retreat—during which time he doubtless trusted that everything would work out fine in the end—McGuinn came back strong (as we shall see in the next instalment) with a carefully executed strategy.

Hillman, largely absent from rock’s commercial radar from 1980-1986, found great success with the Desert Rose Band in the latter half of the decade. This success, however, came after he had changed genre lanes, and headed outta Dodge for the country.

The most surprising rally, however, was mounted by Crosby, who had spent nine months (out of a five-year sentence) in a Texas prison for drugs and weapons offences, yet somehow reemerged as a fully re-energized force: not only did he reinvent/reintroduce himself to old/new fans by penning a successful autobiography, he made a self-lampooning appearance on The Simpsons, and released a generally well-received solo album.

|

Gene Clark, who more or less jettisoned himself from rock’s A-list—on more than one occasion—was pretty much out of the game for good this time. Absent the kind of visionary management/fixers who guided the unlikely comeback of a rotund, outspoken, walrus-moustachioed, aging ‘60s hippie, Gene Clark flailed in many directions, all of which amounted to bupkis.

While other avenues led to dead ends, he never abandoned one particular pursuit, for which we should be grateful.

He kept writing songs.

Comments