Roadmaster/Hinshaw Mix FAQ

Gene Clark — Roadmaster

The Roadmaster/Hinshaw Mix FAQIf you’ve ever read about Gene Clark’s problem-ridden April-June 1972 sessions at Wally Heider Studios—sessions that would ultimately form the backbone of 1973’s Roadmaster compilation—chances are you’ve encountered discussion of what's commonly known as "the Hinshaw mix." But what are we talking about when we use the term? As Gene's popularity grows, a lot of bad information gets shared online. I'm hoping to clear up any confusion with the following FAQ, which is based on what I've seen Facebook, music boards, Instagram, Twitter, et cetera. If, after reading this, you have any questions about the Hinshaw mix, I'd be happy to attempt to answer them, or take steps to contact people whose knowledge exceeds my own. Feel free to leave a comment below and I'll do my best to answer.

So, here we go. In my experience, the following are the most commonly asked questions:

What is the Hinshaw mix?

Why wasn't the Hinshaw mix used?

Who is Hinshaw?

Has the Hinshaw mix been officially released?

What is the Hinshaw mix?

The Hinshaw mix is a rough mix of eight songs recorded between April-June 1972 by producer Chris Hinshaw, Terry Melcher’s assistant, who was enlisted to complete the sessions after Melcher left the project.

The eight songs recorded during Hinshaw's tenure are:

‘Full Circle Song’ | ‘I Remember the Railroad’ | ‘Rough and Rocky’ | ‘She Don’t Care About Time’ | ‘In a Misty Morning’ | ‘Roadmaster’ | ‘I Really Don’t Want to Know’ | ‘Shooting Star’

Why wasn't the Hinshaw mix used?

Before leaving the project (the reasons for which are discussed below) Hinshaw created an eight-song acetate that featured his rough mix of completed work. Since Chris Hinshaw's work was limited to these eight songs, it is therefore a mistake to use the term "Hinshaw mix" when referring to any other song or mix related to the Roadmaster era.

When Jim Dickson took it upon himself to resurrect the project, he decided to disregard the mixes created by Hinshaw, and created the familiar mix that has been available since Roadmaster was first released on the Dutch Ariola label in 1973.

Has the Hinshaw mix been officially released?

Short answer: Not all eight songs, no, but a few have slipped out in a convoluted, typically Clarkesque fashion.

Hinshaw’s alternate/rough mix remains officially unreleased in its entirety (although isolated tracks have turned up elsewhere and will be noted in part 2 of this piece), and over time has taken on almost mythical status among fans, many of whom are naturally drawn to the allure of the unheard. Fans’ appetites were further whetted by John Einarson’s enthusiastic championing of Hinshaw’s mix over Dickson’s in his biography of Gene, Mr Tambourine Man, the Life & Legacy of the Byrds’ Gene Clark. Much like the Gene Clark Sings for You acetate, the absence of aural evidence creates a blank space in Gene’s story, vulnerable to the emergence of a fan-driven narrative that offers an exaggerated extrapolation of revelatory aspects of the mix. As with every other aspect of Gene’s life, the answers are never easy. They require context and detail.

As Gene’s fan base continues to grow—thanks, in large part, to the steady stream of excellent archival releases overseen by the always-quality-conscious Clark Estate—a lot of the old stories and legends are being unearthed and shared on social media. It is, of course, wonderful to see widespread interest in all things Gene, but it’s also important to know the facts that gave rise to the legends.

Hinshaw also engineered Sly and the Family Stone’s epochal There’s a Riot Goin’ On. And it was through this fateful relationship with Stone that, as we shall see, Hinshaw would both earn his career’s most prestigious credit, and make (what appears to have been) a career-killing blunder.

Hinshaw also engineered Sly and the Family Stone’s epochal There’s a Riot Goin’ On. And it was through this fateful relationship with Stone that, as we shall see, Hinshaw would both earn his career’s most prestigious credit, and make (what appears to have been) a career-killing blunder.

For whatever reason, Hinshaw’s career seems to have peaked in 1973, with the twin triumphs of Sly and the Family Stone’s Fresh and Gene Clark’s Roadmaster. For reasons that aren’t clear, Hinshaw's career effectively stalled after that. What credits he amassed from 1977 until 1986 were noticeably fewer and farther between than previous, and with less-celebrated artists. However, since the vast majority of them involve acts associated with Hula Records, based in Honolulu, he may have moved out of the LA area during this period. Assuming the information gleaned from Discogs is correct, Chris Hinshaw’s final credit would appear to be on Southern Pacific’s Killbilly Hill album in 1986, though it’s not clear in what specific capacity he served.

For whatever reason, Hinshaw’s career seems to have peaked in 1973, with the twin triumphs of Sly and the Family Stone’s Fresh and Gene Clark’s Roadmaster. For reasons that aren’t clear, Hinshaw's career effectively stalled after that. What credits he amassed from 1977 until 1986 were noticeably fewer and farther between than previous, and with less-celebrated artists. However, since the vast majority of them involve acts associated with Hula Records, based in Honolulu, he may have moved out of the LA area during this period. Assuming the information gleaned from Discogs is correct, Chris Hinshaw’s final credit would appear to be on Southern Pacific’s Killbilly Hill album in 1986, though it’s not clear in what specific capacity he served.

Sadly, Christopher Alfred Hinshaw was killed on April 30, 2004, in a single-vehicle accident on Hickory Hollow Parkway in Nashville, Davidson County, Tennessee. He was 58 years old.

Did Chris Hinshaw produce all of Roadmaster?

No, Hinshaw produced the 1972 sessions, specifically songs 4-11 on the LP, when it was released in 1973. Jim Dickson produced tracks 1-3.

Why were the Roadmaster sessions abandoned?

It’s a pity that Hinshaw is not here to respond to accusations that it was largely his fault that the 1972 sessions came to a premature end. But the oft-repeated story goes like this: at some point in the sessions—and, significantly, on a day Gene was not present—Hinshaw invited Sly Stone to the studio. His motives for doing so are not known, but as mentioned, he had worked with Sly on There’s a Riot Goin’ On, released the previous year; he also would end up working on Stone’s 1973 LP, Fresh, so it does not strain credulity to wonder if he was angling for his next gig before completing his current one. In any event, Stone, who arrived with an entourage, is alleged to have essentially commandeered the studio, and in so doing run up significant charges, all of which wound up on Gene Clark’s account…which in turn left A&M Records on the hook.

Assuming the above is true, Hinshaw is justly blamed for his failure to maintain order and take control of the situation, especially since it was he who instigated it. Not only was this a shocking lapse of professional judgement on his part, it was a total betrayal of Gene Clark, whose best interests he was presumably hired to represent, to the best of his ability.

As we know, Gene's project had been initially upended by Terry Melcher's decision to bow out of the sessions (apparently due to lingering emotional toll wrought by his proximity to the infamous Tate-LaBianca murders and injuries suffered in a serious car crash). What is never pointed out here is Gene's magnanimity in allowing Melcher’s assistant to be catapulted onboard and entrusted to steer the ship. Hinshaw betrayed that trust.

Unfortunately, the decision ended up costing Gene in more ways than one.

Rick Clark, Gene’s brother, told John Einarson that this “fiasco” effectively “doomed that record.” He went on to say: “I blame Chris Hinshaw for all that because he was the one who called Sly and had him come down. It got really weird. Clarence [White] and I got really disgusted, and he packed up his guitars and left.” Add to that a comment from Jim Dickson, who said the young engineer-cum-producer was “too spaced out and the album never got finished,” and it becomes apparent that the contretemps surrounding Hinshaw’s conduct delivered the album’s coups de grâce. After all, without A&M’s support, there was no album to complete.

How did the Hinshaw mixes differ from the released mix? Is it better?

For my take on this, stay tuned for Part 2 of this piece in which I'll answer the theoretical question: “How would I compile the definitive Deluxe Edition of Roadmaster”?

So in this post I'll tackle all of the above, plus some logical follow-up questions.

The Hinshaw mix is a rough mix of eight songs recorded between April-June 1972 by producer Chris Hinshaw, Terry Melcher’s assistant, who was enlisted to complete the sessions after Melcher left the project.

The eight songs recorded during Hinshaw's tenure are:

‘Full Circle Song’ | ‘I Remember the Railroad’ | ‘Rough and Rocky’ | ‘She Don’t Care About Time’ | ‘In a Misty Morning’ | ‘Roadmaster’ | ‘I Really Don’t Want to Know’ | ‘Shooting Star’

Why wasn't the Hinshaw mix used?

Before leaving the project (the reasons for which are discussed below) Hinshaw created an eight-song acetate that featured his rough mix of completed work. Since Chris Hinshaw's work was limited to these eight songs, it is therefore a mistake to use the term "Hinshaw mix" when referring to any other song or mix related to the Roadmaster era.

When Jim Dickson took it upon himself to resurrect the project, he decided to disregard the mixes created by Hinshaw, and created the familiar mix that has been available since Roadmaster was first released on the Dutch Ariola label in 1973.

Has the Hinshaw mix been officially released?

Short answer: Not all eight songs, no, but a few have slipped out in a convoluted, typically Clarkesque fashion.

Hinshaw’s alternate/rough mix remains officially unreleased in its entirety (although isolated tracks have turned up elsewhere and will be noted in part 2 of this piece), and over time has taken on almost mythical status among fans, many of whom are naturally drawn to the allure of the unheard. Fans’ appetites were further whetted by John Einarson’s enthusiastic championing of Hinshaw’s mix over Dickson’s in his biography of Gene, Mr Tambourine Man, the Life & Legacy of the Byrds’ Gene Clark. Much like the Gene Clark Sings for You acetate, the absence of aural evidence creates a blank space in Gene’s story, vulnerable to the emergence of a fan-driven narrative that offers an exaggerated extrapolation of revelatory aspects of the mix. As with every other aspect of Gene’s life, the answers are never easy. They require context and detail.

As Gene’s fan base continues to grow—thanks, in large part, to the steady stream of excellent archival releases overseen by the always-quality-conscious Clark Estate—a lot of the old stories and legends are being unearthed and shared on social media. It is, of course, wonderful to see widespread interest in all things Gene, but it’s also important to know the facts that gave rise to the legends.

|

| Above: Chris Hinshaw, circa 1971 |

Who is Chris Hinshaw?

The idea to create a Hinshaw mix FAQ came to me this summer, when I was struck by the sudden realization that not only did I know very little about this pivotal figure, I did not even know what Chris Hinshaw looked like!

And when a simple Google search turned up nothing, I figured it was incumbent upon me to do my due diligence before attempting to write the Hinshaw mix FAQ, lest I be accused of spreading bad info. Alas, even after receiving game-changing information from an anonymous source that effectively kickstarted my research (see photo at left) many questions remain unanswered.

And when a simple Google search turned up nothing, I figured it was incumbent upon me to do my due diligence before attempting to write the Hinshaw mix FAQ, lest I be accused of spreading bad info. Alas, even after receiving game-changing information from an anonymous source that effectively kickstarted my research (see photo at left) many questions remain unanswered.

Elsewhere, attempts to contact Hinshaw’s daughters have been unsuccessful. My research is ongoing, so the following will be revised as new information is uncovered. But here is what I have learned:

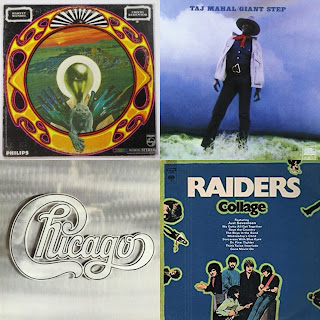

Recording engineer and producer Chris Hinshaw was born on January 15, 1946, in Woodland Hills, Los Angeles County, California. By the age of 23 he had earned engineering credits on a pair of late ‘60s blues-rock classics: Harvey Mandel’s Cristo Redentor (1968); and Taj Mahal’s legendary double set, Giant Step/De Ole Folks at Home (1969). It’s worth noting these were his first professional credits. After that impressive one-two combination, Hinshaw worked steadily—and with some fairly big names, including Chicago (Chicago II, 1970); The Byrds’ (Untitled) and Byrdmaniax (1970 and ’71 respectively, working alongside Terry Melcher). [Interesting Gene Clark-related fact: Hinshaw worked with the Raiders (formerly Paul Revere and the Raiders) on their 1970 LP, Collage. Conscripted into the by-then depleted ranks of the Raiders, reduced to the duo of Paul Revere and Mark Lindsay, was none other than Freddy Weller, who penned and recorded the titular track to the Gene Clark album that Hinshaw would go on to produce.]

Hinshaw also engineered Sly and the Family Stone’s epochal There’s a Riot Goin’ On. And it was through this fateful relationship with Stone that, as we shall see, Hinshaw would both earn his career’s most prestigious credit, and make (what appears to have been) a career-killing blunder.

Hinshaw also engineered Sly and the Family Stone’s epochal There’s a Riot Goin’ On. And it was through this fateful relationship with Stone that, as we shall see, Hinshaw would both earn his career’s most prestigious credit, and make (what appears to have been) a career-killing blunder.  For whatever reason, Hinshaw’s career seems to have peaked in 1973, with the twin triumphs of Sly and the Family Stone’s Fresh and Gene Clark’s Roadmaster. For reasons that aren’t clear, Hinshaw's career effectively stalled after that. What credits he amassed from 1977 until 1986 were noticeably fewer and farther between than previous, and with less-celebrated artists. However, since the vast majority of them involve acts associated with Hula Records, based in Honolulu, he may have moved out of the LA area during this period. Assuming the information gleaned from Discogs is correct, Chris Hinshaw’s final credit would appear to be on Southern Pacific’s Killbilly Hill album in 1986, though it’s not clear in what specific capacity he served.

For whatever reason, Hinshaw’s career seems to have peaked in 1973, with the twin triumphs of Sly and the Family Stone’s Fresh and Gene Clark’s Roadmaster. For reasons that aren’t clear, Hinshaw's career effectively stalled after that. What credits he amassed from 1977 until 1986 were noticeably fewer and farther between than previous, and with less-celebrated artists. However, since the vast majority of them involve acts associated with Hula Records, based in Honolulu, he may have moved out of the LA area during this period. Assuming the information gleaned from Discogs is correct, Chris Hinshaw’s final credit would appear to be on Southern Pacific’s Killbilly Hill album in 1986, though it’s not clear in what specific capacity he served.Sadly, Christopher Alfred Hinshaw was killed on April 30, 2004, in a single-vehicle accident on Hickory Hollow Parkway in Nashville, Davidson County, Tennessee. He was 58 years old.

Did Chris Hinshaw produce all of Roadmaster?

|

| Above: With credits like Sly and the Family Stone's There's a Riot Goin' On and Fresh (above left) Chris Hinshaw's career appeared to be on the ascent in the early 1970s. What happened? |

Why were the Roadmaster sessions abandoned?

It’s a pity that Hinshaw is not here to respond to accusations that it was largely his fault that the 1972 sessions came to a premature end. But the oft-repeated story goes like this: at some point in the sessions—and, significantly, on a day Gene was not present—Hinshaw invited Sly Stone to the studio. His motives for doing so are not known, but as mentioned, he had worked with Sly on There’s a Riot Goin’ On, released the previous year; he also would end up working on Stone’s 1973 LP, Fresh, so it does not strain credulity to wonder if he was angling for his next gig before completing his current one. In any event, Stone, who arrived with an entourage, is alleged to have essentially commandeered the studio, and in so doing run up significant charges, all of which wound up on Gene Clark’s account…which in turn left A&M Records on the hook.

Assuming the above is true, Hinshaw is justly blamed for his failure to maintain order and take control of the situation, especially since it was he who instigated it. Not only was this a shocking lapse of professional judgement on his part, it was a total betrayal of Gene Clark, whose best interests he was presumably hired to represent, to the best of his ability.

As we know, Gene's project had been initially upended by Terry Melcher's decision to bow out of the sessions (apparently due to lingering emotional toll wrought by his proximity to the infamous Tate-LaBianca murders and injuries suffered in a serious car crash). What is never pointed out here is Gene's magnanimity in allowing Melcher’s assistant to be catapulted onboard and entrusted to steer the ship. Hinshaw betrayed that trust.

Unfortunately, the decision ended up costing Gene in more ways than one.

Rick Clark, Gene’s brother, told John Einarson that this “fiasco” effectively “doomed that record.” He went on to say: “I blame Chris Hinshaw for all that because he was the one who called Sly and had him come down. It got really weird. Clarence [White] and I got really disgusted, and he packed up his guitars and left.” Add to that a comment from Jim Dickson, who said the young engineer-cum-producer was “too spaced out and the album never got finished,” and it becomes apparent that the contretemps surrounding Hinshaw’s conduct delivered the album’s coups de grâce. After all, without A&M’s support, there was no album to complete.

But it’s also interesting to note, even apart from the Hinshaw-Stone incident, the perfect storm that was gathering around this album. In retrospect, it seemed doomed from the start.

But don't take my word for it; John Einarson made the same observation in his biography of Gene: “Roger’s presence [at the 1972 sessions] was, in fact, a harbinger of things to come and one of the reasons the sessions would ultimately be abandoned.” Well, I wouldn’t go that far. I’d submit A&M's pulling the plug on the project was the most significant factor in the demise of the original Roadmaster project, but an obvious question that no one has apparently ever asked is: where exactly was Gene that day when things got out of control? Why was he absent? Rick Clark says he and Clarence White were there. It seems a bit out of character, especially when one remembers musicians’ testimonials to Gene’s focused presence throughout the No Other sessions. Had he already mentally checked out, moved on to the Byrds reunion? Was he jamming with Roger? The Byrds reunion promised a huge payday. With a young family to support, who could blame him for following the money? And Gene had a well-established pattern of moving on suddenly (as people like Laramy Smith found out).

|

| Familiar faces made up the core band of the 1972 sessions Chris Ethridge (top) Clockwise, from left— Byron Berline; (Chris Hillman) Sneaky Pete Kleinow, Michael Clarke; Clarence White. |

1972 was an extraordinarily busy year for Gene. There were many variables at play, in a constantly shifting dynamic. Take, for example, the uncredited presence of Roger McGuinn at the sessions (he is heard quite clearly on the Hinshaw mix). By dint of his appearance at this specific juncture, juxtaposed with momentous events that would follow soon thereafter, it’s not a stretch to say that whispers of a Byrds reunion might’ve caused Gene to lose a bit of focus.

But don't take my word for it; John Einarson made the same observation in his biography of Gene: “Roger’s presence [at the 1972 sessions] was, in fact, a harbinger of things to come and one of the reasons the sessions would ultimately be abandoned.” Well, I wouldn’t go that far. I’d submit A&M's pulling the plug on the project was the most significant factor in the demise of the original Roadmaster project, but an obvious question that no one has apparently ever asked is: where exactly was Gene that day when things got out of control? Why was he absent? Rick Clark says he and Clarence White were there. It seems a bit out of character, especially when one remembers musicians’ testimonials to Gene’s focused presence throughout the No Other sessions. Had he already mentally checked out, moved on to the Byrds reunion? Was he jamming with Roger? The Byrds reunion promised a huge payday. With a young family to support, who could blame him for following the money? And Gene had a well-established pattern of moving on suddenly (as people like Laramy Smith found out).

The only problem with that explanation is that the sessions for the reunion did not take place until October of 1972 –– a full four months after the original Roadmaster ground to a halt.

But if a potential Byrds reunion added one distraction/complication, yet another came in the form of Jim Dickson, who reappeared on the scene with the (frankly harebrained) idea of having Gene re-record vocals of tracks from his first album (the ill-fated Early L.A. Sessions project, 1972) –– a stunt that took up precious time, and went nowhere.

Clearly, Gene Clark had a lot going on in 1972; the possibility exists that he may have been overtasked. A&M's decision to slam the brakes on Roadmaster may have given him some breathing room to pursue the lucrative Byrds reunion, but it doesn't mean he abandoned the project. How could he abandon it, if A&M had already abandoned him?

Hinshaw’s failure to assert control in the Sly Stone incident was, in my opinion, egregious. It was careless abrogation of his duties as producer, and the fatal final blow to the Roadmaster sessions proper.

After A&M made the decision to pull the plug on the project, there wasn't much Gene could do, so he simply moved on.

How did the Hinshaw mixes differ from the released mix? Is it better?

For my take on this, stay tuned for Part 2 of this piece in which I'll answer the theoretical question: “How would I compile the definitive Deluxe Edition of Roadmaster”?

If you’ve enjoyed reading this piece, kindly consider making a small donation to my continuing work on this blog.

Comments

I downloaded the mixes, but I did not see any comments on the source.

What are your thoughts on these?

I am also a huge fan of Clarence White and constantly searching for recordings on which you can get him to stretch out. Thanks