A Time to Gain, A Time to Lose...Time: ‘She Don't Care About Time’

‘She Don’t Care About Time’ (Gene Clark) |

|

| Above: ‘She Don’t Care About Time’ graced the B-side of another time-themed song, ‘Turn! Turn! Turn!’ — the group’s second #1 of 1965. |

“Maybe someone can explain time”

— ‘Some Misunderstanding’ (1974)

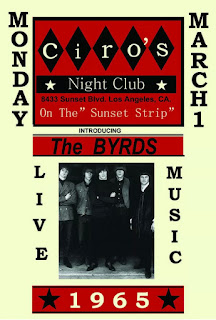

The Byrds 1965: From Ciro’s to Heroes

|

| Ciro’s poster promoting appearance by then-new group on the Strip, The Byrds. |

But at that specific time it had to have appeared, at least to anyone paying attention, that Gene Clark was on a roll. Seemingly entrenched as the Byrds’ principal songwriter, he was young, handsome, and blessed with an uncanny ability to write a steady stream of quality songs (the Byrds’ debut featured three Clark originals and two co-writes). Astonishingly, even while caught in the now-infamous cycle of touring-recording-touring that’s proved the undoing of many songwriters (the “sophomore slump”), Gene presented a clutch of impressive new songs for Turn! Turn! Turn!, the Byrds’ second LP. They toured England, met the Beatles, opened for the Rolling Stones in the US. And then, on December 12, 1965, the Byrds capped off one of the greatest success stories in rock, when the walked onto the hallowed stage of the Ed Sullivan Theatre to perform their back-to-back #1 hits.

Not a bad year’s work, really—but that doesn’t even begin to list Gene Clark’s personal accomplishments as a songwriter. At the very moment he took Sullivan’s stage that day, Gene had already recorded or written an entirely new batch of songs, all of which demonstrated stunning growth: ‘That’s What You Want,’ ‘Eight Miles High,’ ‘The Day Walk,’ and ‘She Don’t Care About Time.’ Each song was a proverbial giant leap forward, especially when compared to 1964’s likeable-but-derivative stompers, like ‘Boston’ and ‘You Movin’.’1

|

| From Ciro’s to Heroes: Screengrabs of Gene Clark from The Byrds’ appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, December 12, 1965. |

The Song Not the Singer

In many ways, ‘She Don’t Care About Time’ was the best of them all. It is fresh, imaginative and invigorating. And while the Byrds’ version is definitive2, this piece is intended to stress the song and its writer, not the singer(s) (with apologies to the Rolling Stones). Its construction is flawless. It stands as evidence of the Byrds’ true magnificence as a group: a moment in time at which their disparate backgrounds and conflicting personalities were overpowered by the glory of the music they created.

It was a personal triumph for Gene Clark.

As a composition, ‘She Don’t Care About Time’ dignifies any genre or arrangement—but you needn’t take my word for it. Think of any random song and try to imagine how it would sound, played in other styles. It’s not always an option. I often think of the song as a living entity unto itself; it breathes and speaks of the composer’s brilliance; it is imprinted with Gene’s DNA. It is not necessarily dependent upon, nor tethered to, a particular riff (with apologies to Roger’s Rickenbacker) or studio trickery that might prove difficult to replicate in a live setting.

It is among the most sublime songs in the Byrds’ entire catalogue, and a revelation as to the scope of Gene’s poetic aspirations: at its core, it speaks to the irrelevance of time as a construct; one that is susceptible to a poetic end-run. Extrapolating that thought, one might dare to view it as Gene Clark’s bid for immortality.

Over the course of his career, Gene himself demonstrated the song’s versatility by presenting it in no fewer than three different guises, separate from the nascent power-pop version made famous by the Byrds: on 1973’s Roadmaster, it took the form of a slow country weeper (see link below); in the mid-‘70s, the Silverados recast it as breezy California MOR.

In late-period live performances, Gene brought the song full circle. On the posthumously released Silhouetted in Light (1992) Gene performed it as it was doubtless composed—solo. It may be initially off-putting to hear the joyously winding melody stripped of its harmonies and youthful exuberance, “chiselled by pain,” presented as a sepulchral dirge.

But listen again.

It is a song written by a young man, played by his older self. In his voice one detects the toll taken by time along the road of excess. If the corporeal man failed to reach the palace of wisdom during his time, this stirring performance stands as a reminder that true artistry transcends time.

And therein stands the palace of his poetic wisdom.

|

| Above: The Byrds on the Ed Sullivan Show, December 12, 1965. |

The Byrds’ take on the song is a thrilling piece of power-pop that predated coinage of the term. McGuinn’s distinctive Rickenbacker riff and Michael Clarke’s serviceable take on Ringo’s ‘Ticket to Ride’ beat are both noteworthy. But it’s those trademark Byrds vocals, wrapped around Gene’s mesmerizing melody, that command most attention. In the hands of the Byrds, the song became an showcase for Clark, Crosby and McGuinn, in that no single voice sang lead (as opposed to, say, ‘I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better,’ which featured Gene as lead singer with Crosby and McGuinn adding backup). The Byrds, whom Crosby once said could sing like angels, were certainly blessed from above on the day they cut this song. The Byrds’ version, in fact, sounds so glorious that it might tend to overshadow Clark’s lyrical ambitions.

And what to make of those lyrics? It’s debatable, of course, but when heard against the circular clang of McGuinn’s riff, the image of someone dashing up a flight of stairs to reach a “white-walled room out on the end of time”certainly feels like an early stab at a psychedelic turn of phrase. But it’s much more than that. The majesty of the song lies in Clark’s inspired metaphysical conceit: those who dwell within the white-walled room are not so much untouched by time as beyond it, on another plane of existence. The white-walled room is untouched, pure, sacred. Time is no real threat to the lovers’ bliss; it is easily circumvented. Reality and, in fact, eternity, is what exists within the white-walled room, much like John Donne’s transformation of a bedroom into an “everywhere” in “The Good Morrow”:

Which watch not one another out of fear;

For love all love of other sights controls,

And makes one little room an everywhere.

Here, “an everywhere” carries the same logistical significance as Clark’s “end of time”: the private moments shared within “one little room” and the “white-walled room” sustain the lovers everywhere they go, and through good times and hardship (“I laugh with her, cry with her”).

The woman in the song is characterized as calm and confident (“she walks with ease”), understanding, and non-judgemental (“all she sees is never wrong or right”). She is satisfied by the substance of a man’s character, rather than searching out a man of substance (“she don’t have to be assured of many good things to find”). From these lines, one may also infer a great deal about the narrator’s character. Clearly he appreciates these qualities in her—especially the last. Perhaps he, like the poor boy in the Brigands’ 1966 song, ‘(Would I Still Be) Her Big Man’, fears being exposed as impoverished; that his worth as a man might be determined by his material wealth, or lack thereof. It’s pretty much the same idea (roles reversed) that Paul McCartney tried to communicate in ‘She’s a Woman’ (“My love don’t give me presents/I know that she’s no peasant”), only Clark accomplishes it without using such crude language. McCartney’s line had none of Clark’s poetic lilt, or courtly respect for his lover. Conversely, Clark may have written the line from the perspective of a wealthy man, who has fallen victim to someone attracted more by the man’s money than the man himself. Remember, the sudden deluge of composer’s royalties that came Gene’s way (after ‘I Knew I’d Want You’ graced the B-side of a number-one single, ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’) might have, at some point, attracted the attention of materialistic women.

The single greatest line in the song is saved for the end: “And with her arms around me tight, I see her all in my mind.” While it’s true that many of Gene Clark’s greatest songs deal with romantic heartbreak, documented here is a moment of pure romantic joy in which, if only for a fleeting moment, the corporeal world (felt in an embrace) connects with his lover’s essence (“I see her all in my mind”) in creation of a perfect moment on a sublimated plane—not in time, but beyond it, out on its edge, where even the very concept is both quaint and irrelevant.

An imaginative escape from clock-related responsibilities and obligations in the context of a song is one thing, but the real-life, clock-watching pressures of being a Byrd was quite another. So with the climactic December 12, 1965 appearance on Ed Sullivan, the Byrds made a powerful statement that put the exclamation mark on a successful year. The were now bona fide stars.

But astonishingly, less than three months later, in a moment that has never been fully analyzed, explained, or examined, Gene Clark inexplicably left the band. His time in the Byrds had run out.

The Byrds - ‘She Don’t Care About Time’

Links to notable cover versions:

Chris Hillman Flamin’ Groovies Michael Carpenter & the Banks Brothers

Richie Furay Skydiggers World Cryan’ Shames

- The big exception to this, however, is another World Pacific demo, ‘Tomorrow is a Long Ways Away,’ which stands as an intriguing predecessor of ‘She Don’t Care About Time.’ The song’s title suggests an acknowledgement of clock-related responsibilities of the near-future, but then Gene’s crooning middle eight suggests possibilities of a union beyond time: “If you will stay here with me forever/I want you to know that my love for you will never die.”

- There are three different recordings of SDCAT: 1) the 45 B-side; 2) Version 1 (included on first Byrds box set and bonus track on 1996 remaster of Turn! Turn! Turn!; 3) Version 2 (included on Sundazed’s The Columbia Singles ‘65-‘67, see image below). At some point I’d like to compare the performances of each, but will save that for a standalone post.

Comments

A fine example of the way Clark eroticizes the urban landscape. Someday I may write a paper on this - I've always meant to.

I'm not 100% certain, but I think Hal only played on the 'Mr. Tambourine Man'/'I Knew I'd Want You' single. I've always thought the Turn Turn Turn album was all Michael. You don't hear the 'Ticket to Ride' influence there? Compared to Ringo's steady hand I think Michael was a little shaky. Still loved him though.

- PsychFan (Jeff)

[gram ended up with a marked dislike for michael clarke= a bit of gossip i retained.]

good post clarkophile! damn! was gene special...

I posted a short tribute to Gene on my blog yesterday, which was the date of his untimely death. I hope you have a chance to check it out.

-smith

Garrett

PS: The Cateran [Scotish Band] cover of this tune is not half bad!

Roger McGuinn's guitar solo is actually Bach's "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring"! ! Gene Clark reportedly did not like it, so he recorded a different version without the solo later on.

It is a lovely song.

Brooke BFA